Global Warming From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

See as well, at least:

- Carbon Footprint From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- Carbon Tax From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- Scientific Opinion on Climate Change From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

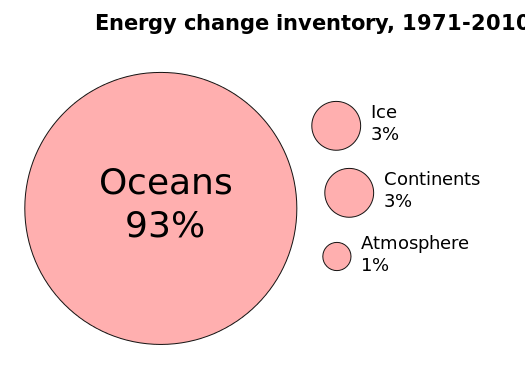

Multiple lines of scientific evidence show that the climate system is warming. Although the increase of near-surface atmospheric temperature is the measure of global warming often reported in the popular press, most of the additional energy stored in the climate system since 1970 has gone into ocean warming. The remainder has melted ice, and warmed the continents and atmosphere. Many of the observed changes since the 1950s are unprecedented over decades to millennia.

Scientific understanding of global warming is increasing. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported in 2014 that scientists were more than 95% certain that global warming is being caused mostly by increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases and other human (anthropogenic) activities. Climate model projections summarized in the report indicated that during the 21st century the global surface temperature is likely to rise a further 0.3 to 1.7 °C (0.5 to 3.1 °F) for their lowest emissions scenario using stringent mitigation and 2.6 to 4.8 °C (4.7 to 8.6 °F) for their highest. These findings have been recognized by the national science academies of the major industrialized nations and are not disputed by any scientific body of national or international standing.

|

| Fossil fuel related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions over the 20th century. Image source: EPA. |

Possible societal responses to global warming include mitigation by emissions reduction, adaptation to its effects, building systems resilient to its effects, and possible future climate engineering. Most countries are parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), whose ultimate objective is to prevent dangerous anthropogenic climate change. The UNFCCC have adopted a range of policies designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to assist in adaptation to global warming. Parties to the UNFCCC have agreed that deep cuts in emissions are required, and that future global warming should be limited to below 2.0 °C (3.6 °F) relative to the pre-industrial level.

On 12 November 2015, NASA scientists reported that human-made carbon dioxide (CO2) continues to increase above levels not seen in hundreds of thousands of years: currently, about half of the carbon dioxide released from the burning of fossil fuels remains in the atmosphere and is not absorbed by vegetation and the oceans.

Observed Temperature Changes

The average temperature of the lower troposphere has increased between 0.13 and 0.22 °C (0.23 and 0.40 °F) per decade since 1979, according to satellite temperature measurements. Climate proxies show the temperature to have been relatively stable over the one or two thousand years before 1850, with regionally varying fluctuations such as the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age.

The warming that is evident in the instrumental temperature record is consistent with a wide range of observations, as documented by many independent scientific groups. Examples include sea level rise, widespread melting of snow and land ice, increased heat content of the oceans, increased humidity, and the earlier timing of spring events, e.g., the flowering of plants. The probability that these changes could have occurred by chance is virtually zero.

Trends

Temperature changes vary over the globe. Since 1979, land temperatures have increased about twice as fast as ocean temperatures (0.25 °C per decade against 0.13 °C per decade). Ocean temperatures increase more slowly than land temperatures because of the larger effective heat capacity of the oceans and because the ocean loses more heat by evaporation. Since the beginning of industrialisation the temperature difference between the hemispheres has increased due to melting of sea ice and snow in the North. Average arctic temperatures have been increasing at almost twice the rate of the rest of the world in the past 100 years; however arctic temperatures are also highly variable. Although more greenhouse gases are emitted in the Northern than Southern Hemisphere this does not contribute to the difference in warming because the major greenhouse gases persist long enough to mix between hemispheres.

The thermal inertia of the oceans and slow responses of other indirect effects mean that climate can take centuries or longer to adjust to changes in forcing. Climate commitment studies indicate that even if greenhouse gases were stabilized at year 2000 levels, a further warming of about 0.5 °C (0.9 °F) would still occur.

Global temperature is subject to short-term fluctuations that overlay long-term trends and can temporarily mask them. The relative stability in surface temperature from 2002 to 2009, which has been dubbed the global warming hiatus by the media and some scientists, is consistent with such an episode. Recent updates to account for differing methods of measuring ocean surface temperature measurements show a significant positive trend over the recent decade.

Warmest Years

Fourteen of the fifteen hottest years have been in the 21st century. While record-breaking years can attract considerable public interest, individual years are less significant than the overall trend. So some climatologists have criticized the attention that the popular press gives to "warmest year" statistics; for example, Gavin Schmidt stated "the long-term trends or the expected sequence of records are far more important than whether any single year is a record or not."

Statistical uncertainty means that it is hard to separate years where the temperatures are close, so while 2014 had a greater chance than any other single year, it only has a 38% to 48% likelihood of being the warmest year on record since 1880. 2014 was the 38th consecutive year with above-average temperatures. Ocean oscillations like El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) can affect global average temperatures, for example, 1998 temperatures were significantly enhanced by strong El Niño conditions. 1998 remained the warmest year until 2005 and 2010 and the temperature of both of these years was enhanced by El Niño periods. However, 2014 was ENSO neutral.

Initial Causes of Temperature Changes (External Forcings)

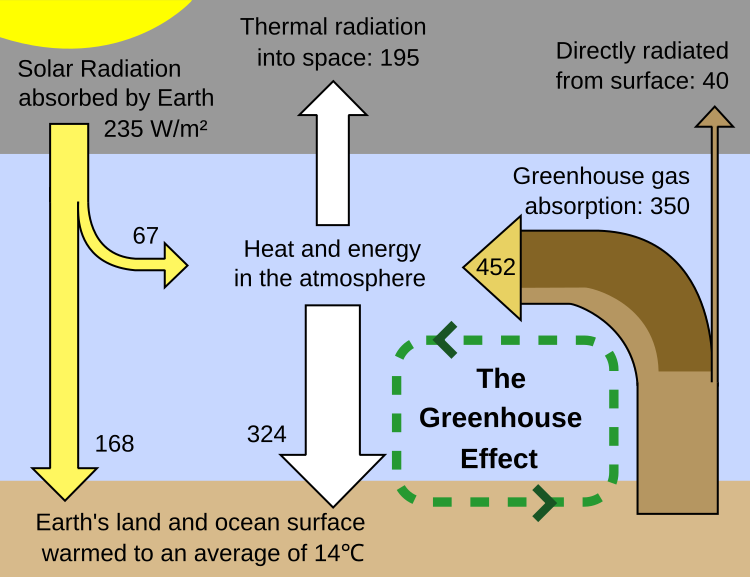

|

| Greenhouse effect schematic showing energy flows between space, the atmosphere, and Earth's surface. Energy exchanges are expressed in watts per square meter (W/m2). |

Greenhouse Gases

The greenhouse effect is the process by which absorption and emission of infrared radiation by gases in a planet's atmosphere warm its lower atmosphere and surface. It was proposed by Joseph Fourier in 1824, discovered in 1860 by John Tyndall, was first investigated quantitatively by Svante Arrhenius in 1896, and was developed in the 1930s through 1960s by Guy Stewart Callendar.

_png.png) |

| Annual world greenhouse gas emissions, in 2010, by sector. |

|

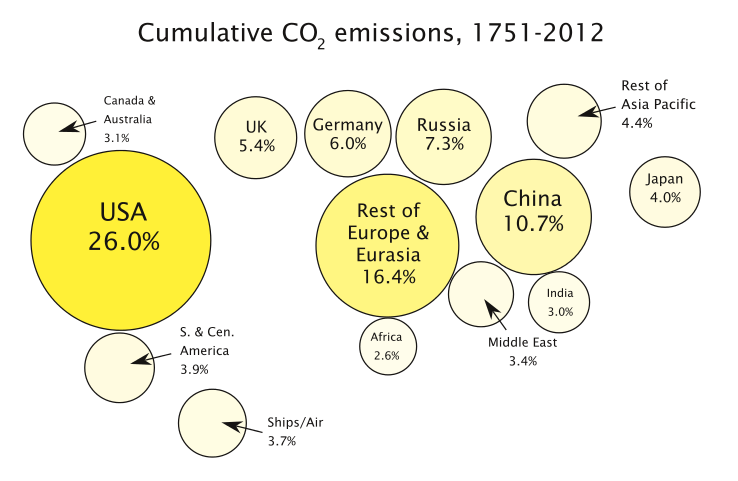

| Percentage share of global cumulative energy-related CO2 emissions between 1751 and 2012 across different regions. |

On 12 November 2015, NASA scientists reported that human-made carbon dioxide (CO2) continues to increase above levels not seen in hundreds of thousands of years: currently, about half of the carbon dioxide released from the burning of fossil fuels remains in the atmosphere and is not absorbed by vegetation and the oceans.

Over the last three decades of the twentieth century, gross domestic product per capita and population growth were the main drivers of increases in greenhouse gas emissions. CO2 emissions are continuing to rise due to the burning of fossil fuels and land-use change. Emissions can be attributed to different regions. Attribution of emissions due to land-use change is a controversial issue.

Emissions scenarios, estimates of changes in future emission levels of greenhouse gases, have been projected that depend upon uncertain economic, sociological, technological, and natural developments. In most scenarios, emissions continue to rise over the century, while in a few, emissions are reduced. Fossil fuel reserves are abundant, and will not limit carbon emissions in the 21st century. Emission scenarios, combined with modelling of the carbon cycle, have been used to produce estimates of how atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases might change in the future. Using the six IPCC SRES "marker" scenarios, models suggest that by the year 2100, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 could range between 541 and 970 ppm. This is 90–250% above the concentration in the year 1750.

The popular media and the public often confuse global warming with ozone depletion, i.e., the destruction of stratospheric ozone (e.g., the ozone layer) by chlorofluorocarbons. Although there are a few areas of linkage, the relationship between the two is not strong. Reduced stratospheric ozone has had a slight cooling influence on surface temperatures, while increased tropospheric ozone has had a somewhat larger warming effect.

Aerosols and Soot

Global dimming, a gradual reduction in the amount of global direct irradiance at the Earth's surface, was observed from 1961 until at least 1990. Solid and liquid particles known as aerosols, produced by volcanoes and human-made pollutants, are thought to be the main cause of this dimming. They exert a cooling effect by increasing the reflection of incoming sunlight. The effects of the products of fossil fuel combustion – CO2 and aerosols – have partially offset one another in recent decades, so that net warming has been due to the increase in non-CO2 greenhouse gases such as methane. Radiative forcing due to aerosols is temporally limited due to the processes that remove aerosols from the atmosphere. Removal by clouds and precipitation gives tropospheric aerosols an atmospheric lifetime of only about a week, while stratospheric aerosols can remain for a few years. Carbon dioxide has a lifetime of a century or more, and as such, changes in aerosols will only delay climate changes due to carbon dioxide. Black carbon is second only to carbon dioxide for its contribution to global warming.

In addition to their direct effect by scattering and absorbing solar radiation, aerosols have indirect effects on the Earth's radiation budget. Sulfate aerosols act as cloud condensation nuclei and thus lead to clouds that have more and smaller cloud droplets. These clouds reflect solar radiation more efficiently than clouds with fewer and larger droplets, a phenomenon known as the Twomey effect. This effect also causes droplets to be of more uniform size, which reduces growth of raindrops and makes the cloud more reflective to incoming sunlight, known as the Albrecht effect. Indirect effects are most noticeable in marine stratiform clouds, and have very little radiative effect on convective clouds. Indirect effects of aerosols represent the largest uncertainty in radiative forcing.

Soot may either cool or warm Earth's climate system, depending on whether it is airborne or deposited. Atmospheric soot directly absorbs solar radiation, which heats the atmosphere and cools the surface. In isolated areas with high soot production, such as rural India, as much as 50% of surface warming due to greenhouse gases may be masked by atmospheric brown clouds. When deposited, especially on glaciers or on ice in arctic regions, the lower surface albedo can also directly heat the surface. The influences of atmospheric particles, including black carbon, are most pronounced in the tropics and sub-tropics, particularly in Asia, while the effects of greenhouse gases are dominant in the extratropics and southern hemisphere.

Solar Activity

Climate models have been used to examine the role of the Sun in recent climate change. Models are unable to reproduce the rapid warming observed in recent decades when they only take into account variations in solar output and volcanic activity. Models are, however, able to simulate the observed 20th century changes in temperature when they include all of the most important external forcings, including human influences and natural forcings.

Another line of evidence against the Sun having caused recent climate change comes from looking at how temperatures at different levels in the Earth's atmosphere have changed. Models and observations show that greenhouse warming results in warming of the lower atmosphere (called the troposphere) but cooling of the upper atmosphere (called the stratosphere). Depletion of the ozone layer by chemical refrigerants has also resulted in a strong cooling effect in the stratosphere. If the Sun were responsible for observed warming, warming of both the troposphere and stratosphere would be expected.

Variations in Earth's Orbit

Orbital cycles vary slowly over tens of thousands of years, and at present are in a very slow cooling trend. The variations in orbital cycles may produce a glacial period about 50,000 years from now.

Feedback

|

| Sea ice, shown here in Nunavut, in northern Canada, reflects more sunshine, while open ocean absorbs more, accelerating melting. |

There are a range of feedbacks in the climate system, including water vapor, changes in ice-albedo (snow and ice cover affect how much the Earth's surface absorbs or reflects incoming sunlight), clouds, and changes in the Earth's carbon cycle (e.g., the release of carbon from soil). The main negative feedback is the energy the Earth's surface radiates into space as infrared radiation. According to the Stefan-Boltzmann law, if the absolute temperature (as measured in kelvin) doubles, radiated energy increases by a factor of 16 (2 to the 4th power).

Feedbacks are an important factor in determining the sensitivity of the climate system to increased atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations. Other factors being equal, a higher climate sensitivity means that more warming will occur for a given increase in greenhouse gas forcing. Uncertainty over the effect of feedbacks is a major reason why different climate models project different magnitudes of warming for a given forcing scenario. More research is needed to understand the role of clouds and carbon cycle feedbacks in climate projections.

The IPCC projections previously mentioned span the "likely" range (greater than 66% probability, based on expert judgement) for the selected emissions scenarios. However, the IPCC's projections do not reflect the full range of uncertainty. The lower end of the "likely" range appears to be better constrained than the upper end of the "likely" range.

Climate Models

Although researchers attempt to include as many processes as possible, simplifications of the actual climate system are inevitable because of the constraints of available computer power and limitations in knowledge of the climate system. Results from models can also vary due to different greenhouse gas inputs and the model's climate sensitivity. For example, the uncertainty in IPCC's 2007 projections is caused by (1) the use of multiple models with differing sensitivity to greenhouse gas concentrations, (2) the use of differing estimates of humanity's future greenhouse gas emissions, (3) any additional emissions from climate feedbacks that were not included in the models IPCC used to prepare its report, i.e., greenhouse gas releases from permafrost.

The models do not assume the climate will warm due to increasing levels of greenhouse gases. Instead the models predict how greenhouse gases will interact with radiative transfer and other physical processes. Warming or cooling is thus a result, not an assumption, of the models.

Clouds and their effects are especially difficult to predict. Improving the models' representation of clouds is therefore an important topic in current research. Another prominent research topic is expanding and improving representations of the carbon cycle.

Models are also used to help investigate the causes of recent climate change by comparing the observed changes to those that the models project from various natural and human causes. Although these models do not unambiguously attribute the warming that occurred from approximately 1910 to 1945 to either natural variation or human effects, they do indicate that the warming since 1970 is dominated by man-made greenhouse gas emissions.

The physical realism of models is tested by examining their ability to simulate contemporary or past climates. Climate models produce a good match to observations of global temperature changes over the last century, but do not simulate all aspects of climate. Not all effects of global warming are accurately predicted by the climate models used by the IPCC. Observed Arctic shrinkage has been faster than that predicted. Precipitation increased proportionally to atmospheric humidity, and hence significantly faster than global climate models predict. Since 1990, sea level has also risen considerably faster than models predicted it would.

Observed and Expected Environmental Effects

During the 21st century, glaciers and snow cover are projected to continue their widespread retreat. Projections of declines in Arctic sea ice vary. Recent projections suggest that Arctic summers could be ice-free (defined as ice extent less than 1 million square km) as early as 2025-2030.

"Detection" is the process of demonstrating that climate has changed in some defined statistical sense, without providing a reason for that change. Detection does not imply attribution of the detected change to a particular cause. "Attribution" of causes of climate change is the process of establishing the most likely causes for the detected change with some defined level of confidence. Detection and attribution may also be applied to observed changes in physical, ecological and social systems.

Extreme Weather

Changes in regional climate are expected to include greater warming over land, with most warming at high northern latitudes, and least warming over the Southern Ocean and parts of the North Atlantic Ocean.

Future changes in precipitation are expected to follow existing trends, with reduced precipitation over subtropical land areas, and increased precipitation at subpolar latitudes and some equatorial regions. Projections suggest a probable increase in the frequency and severity of some extreme weather events, such as heat waves.

A 2015 study published in Nature, states: About 18% of the moderate daily precipitation extremes over land are attributable to the observed temperature increase since pre-industrial times, which in turn primarily results from human influence. For 2 °C of warming the fraction of precipitation extremes attributable to human influence rises to about 40%. Likewise, today about 75% of the moderate daily hot extremes over land are attributable to warming. It is the most rare and extreme events for which the largest fraction is anthropogenic, and that contribution increases nonlinearly with further warming.

Data analysis of extreme events from 1960 till 2010 suggests that droughts and heat waves appear simultaneously with increased frequency.

Sea Level Rise

Widespread coastal flooding would be expected if several degrees of warming is sustained for millennia. For example, sustained global warming of more than 2 °C (relative to pre-industrial levels) could lead to eventual sea level rise of around 1 to 4 m due to thermal expansion of sea water and the melting of glaciers and small ice caps. Melting of the Greenland ice sheet could contribute an additional 4 to 7.5 m over many thousands of years. It has been estimated that we are already committed to a sea-level rise of approximately 2.3 meters for each degree of temperature rise within the next 2,000 years.

Warming beyond the 2 °C target would potentially lead to rates of sea-level rise dominated by ice loss from Antarctica. Continued CO2 emissions from fossil sources could cause additional tens of meters of sea level rise, over the next millennia and eventually ultimately eliminate the entire Antarctic ice sheet, causing about 58 meters of sea level rise.

Ecological Systems

In terrestrial ecosystems, the earlier timing of spring events, and poleward and upward shifts in plant and animal ranges, have been linked with high confidence to recent warming. Future climate change is expected to particularly affect certain ecosystems, including tundra, mangroves, and coral reefs. It is expected that most ecosystems will be affected by higher atmospheric CO2 levels, combined with higher global temperatures. Overall, it is expected that climate change will result in the extinction of many species and reduced diversity of ecosystems.

Increases in atmospheric CO2 concentrations have led to an increase in ocean acidity. Dissolved CO2 increases ocean acidity, which is measured by lower pH values. Between 1750 to 2000, surface-ocean pH has decreased by ≈0.1, from ≈8.2 to ≈8.1. Surface-ocean pH has probably not been below ≈8.1 during the past 2 million years. Projections suggest that surface-ocean pH could decrease by an additional 0.3–0.4 units by 2100. Future ocean acidification could threaten coral reefs, fisheries, protected species, and other natural resources of value to society.

Ocean deoxygenation is projected to increase hypoxia by 10%, and triple suboxic waters (oxygen concentrations 98% less than the mean surface concentrations), for each 1 °C of upper Ocean warming.

Seismic Activity

In recent studies, geologists claim that global warming is one of the reasons for increased seismic activity. According to these studies, melting glaciers and rising sea levels disturb the balance of pressure on Earth's tectonic plates thus causing increase in the frequency and intensity of earthquakes.

Long-term Effects

On the timescale of centuries to millennia, the magnitude of global warming will be determined primarily by anthropogenic CO2 emissions. This is due to carbon dioxide's very long lifetime in the atmosphere.

Stabilizing global average temperature would require reductions in anthropogenic CO2 emissions. Reductions in emissions of non-CO2 anthropogenic greenhouse gases (GHGs) (e.g., methane and nitrous oxide) would also be necessary. For CO2, anthropogenic emissions would need to be reduced by more than 80% relative to their peak level. Even if this were achieved, global average temperatures would remain close to their highest level for many centuries.

Large-scale and Abrupt Impacts

Climate change could result in global, large-scale changes in natural and social systems. Two examples are ocean acidification caused by increased atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, and the long-term melting of ice sheets, which contributes to sea level rise.

Some large-scale changes could occur abruptly, i.e., over a short time period, and might also be irreversible. An example of abrupt climate change is the rapid release of methane and carbon dioxide from permafrost, which would lead to amplified global warming. Scientific understanding of abrupt climate change is generally poor. The probability of abrupt change for some climate related feedbacks may be low. Factors that may increase the probability of abrupt climate change include higher magnitudes of global warming, warming that occurs more rapidly, and warming that is sustained over longer time periods.

Observed and Expected Effects on Social Systems

The effects of climate change on human systems, mostly due to warming or shifts in precipitation patterns, or both, have been detected worldwide. Production of wheat and maize globally has been impacted by climate change. While crop production has increased in some mid-latitude regions such as the UK and Northeast China, economic losses due to extreme weather events have increased globally. There has been a shift from cold- to heat-related mortality in some regions as a result of warming. Livelihoods of indigenous peoples of the Arctic have been altered by climate change, and there is emerging evidence of climate change impacts on livelihoods of indigenous peoples in other regions. Regional impacts of climate change are now observable at more locations than before, on all continents and across ocean regions.

The future social impacts of climate change will be uneven. Many risks are expected to increase with higher magnitudes of global warming. All regions are at risk of experiencing negative impacts. Low-latitude, less developed areas face the greatest risk. A study from 2015 concluded that economic growth (Gross domestic product) of poorer countries is much more impaired with projected future climate warming, than previously thought.

A meta analysis of 56 studies concluded in 2014 that each degree of temperature rise will increase violence by up to 20%, which includes fist fights, violent crimes, civil unrest or wars.

Examples of impacts include:

- Food: Crop production will probably be negatively affected in low latitude countries, while effects at northern latitudes may be positive or negative. Global warming of around 4.6 °C relative to pre-industrial levels could pose a large risk to global and regional food security.

- Health: Generally impacts will be more negative than positive. Impacts include: the effects of extreme weather, leading to injury and loss of life; and indirect effects, such as undernutrition brought on by crop failures.

Habitat Inundation

In small islands and mega deltas, inundation as a result of sea level rise is expected to threaten vital infrastructure and human settlements. This could lead to issues of homelessness in countries with low lying areas such as Bangladesh, as well as statelessness for populations in countries such as the Maldives and Tuvalu.

Economy

Estimates based on the IPCC A1B emission scenario from additional CO2 and CH4 greenhouse gases released from permafrost, estimate associated impact damages by US$43 trillion.

Infrastructure

Continued permafrost degradation will likely result in unstable infrastructure in Arctic regions, or Alaska before 2100. Thus, impacting roads, pipelines and buildings, as well as water distribution, and cause slope failures.

Possible Responses to Global Warming

Mitigation

Mitigation of climate change are actions to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, or enhance the capacity of carbon sinks to absorb GHGs from the atmosphere. There is a large potential for future reductions in emissions by a combination of activities, including: energy conservation and increased energy efficiency; the use of low-carbon energy technologies, such as renewable energy, nuclear energy, and carbon capture and storage; and enhancing carbon sinks through, for example, reforestation and preventing deforestation. A 2015 report by Citibank concluded that transitioning to a low carbon economy would yield positive return on investments.

Near- and long-term trends in the global energy system are inconsistent with limiting global warming at below 1.5 or 2 °C, relative to pre-industrial levels. Pledges made as part of the Cancún agreements are broadly consistent with having a likely chance (66 to 100% probability) of limiting global warming (in the 21st century) at below 3 °C, relative to pre-industrial levels.

In limiting warming at below 2 °C, more stringent emission reductions in the near-term would allow for less rapid reductions after 2030. Many integrated models are unable to meet the 2 °C target if pessimistic assumptions are made about the availability of mitigation technologies.

Adaptation

Other policy responses include adaptation to climate change. Adaptation to climate change may be planned, either in reaction to or anticipation of climate change, or spontaneous, i.e., without government intervention. Planned adaptation is already occurring on a limited basis. The barriers, limits, and costs of future adaptation are not fully understood.

A concept related to adaptation is adaptive capacity, which is the ability of a system (human, natural or managed) to adjust to climate change (including climate variability and extremes) to moderate potential damages, to take advantage of opportunities, or to cope with consequences. Unmitigated climate change (i.e., future climate change without efforts to limit greenhouse gas emissions) would, in the long term, be likely to exceed the capacity of natural, managed and human systems to adapt.

Environmental organizations and public figures have emphasized changes in the climate and the risks they entail, while promoting adaptation to changes in infrastructural needs and emissions reductions.

Climate Engineering

Climate engineering (sometimes called by the more expansive term 'geoengineering'), is the deliberate modification of the climate. It has been investigated as a possible response to global warming, e.g. by NASA and the Royal Society. Techniques under research fall generally into the categories solar radiation management and carbon dioxide removal, although various other schemes have been suggested. A study from 2014 investigated the most common climate engineering methods and concluded they are either ineffective or have potentially severe side effects and cannot be stopped without causing rapid climate change.

Discourse About Global Warming

Political Discussion

In ratifying the Kyoto Protocol, most developed countries accepted legally binding commitments to limit their emissions. These first-round commitments expired in 2012. United States President George W. Bush rejected the treaty on the basis that "it exempts 80% of the world, including major population centers such as China and India, from compliance, and would cause serious harm to the US economy."

At the 15th UNFCCC Conference of the Parties, held in 2009 at Copenhagen, several UNFCCC Parties produced the Copenhagen Accord. Parties associated with the Accord (140 countries, as of November 2010):9 aim to limit the future increase in global mean temperature to below 2 °C. The 16th Conference of the Parties (COP16) was held at Cancún in 2010. It produced an agreement, not a binding treaty, that the Parties should take urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to meet a goal of limiting global warming to 2 °C above pre-industrial temperatures. It also recognized the need to consider strengthening the goal to a global average rise of 1.5 °C.

Scientific Discussion

Nearly all scientists agree that humans are contributing to observed climate change. At least 9 surveys of scientists and meta studies of academic papers concerning global warming have been carried out since 2004. While up to 18% of scientists surveyed might disagree with the consensus view, when restricted to scientists publishing in the field of climate, 97 to 100% agreed with the consensus. The consensus view being that most of the current warming is anthropogenic. See Surveys of scientists' views on climate change. National science academies have called on world leaders for policies to cut global emissions.

In the scientific literature, there is a strong consensus that global surface temperatures have increased in recent decades and that the trend is caused mainly by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases. No scientific body of national or international standing disagrees with this view.

Discussion by the Public and in Popular Media

The global warming controversy refers to a variety of disputes, substantially more pronounced in the popular media than in the scientific literature, regarding the nature, causes, and consequences of global warming. The disputed issues include the causes of increased global average air temperature, especially since the mid-20th century, whether this warming trend is unprecedented or within normal climatic variations, whether humankind has contributed significantly to it, and whether the increase is wholly or partially an artifact of poor measurements. Additional disputes concern estimates of climate sensitivity, predictions of additional warming, and what the consequences of global warming will be.

From 1990–1997 in the United States, conservative think tanks mobilized to challenge the legitimacy of global warming as a social problem. They challenged the scientific evidence, argued that global warming will have benefits, and asserted that proposed solutions would do more harm than good.

Some people dispute aspects of climate change science. Organizations such as the libertarian Competitive Enterprise Institute, conservative commentators, and some companies such as ExxonMobil have challenged IPCC climate change scenarios, funded scientists who disagree with the scientific consensus, and provided their own projections of the economic cost of stricter controls. Some fossil fuel companies have scaled back their efforts in recent years, or even called for policies to reduce global warming.

Surveys of Public Opinion

The world public, or at least people in economically advanced regions, became broadly aware of the global warming problem in the late 1980s. Polling groups began to track opinions on the subject, at first mainly in the United States. The longest consistent polling, by Gallup in the US, found relatively small swings of 10% or so from 1998 to 2015 in opinion on the seriousness of global warming, but with increasing polarization between those concerned and those unconcerned.

The first major worldwide poll, conducted by Gallup in 2008-2009 in 127 countries, found that some 62% of people worldwide said they knew about global warming. In the advanced countries of North America, Europe and Japan, 90% or more knew about it (97% in the U.S., 99% in Japan); in less developed countries, especially in Africa, fewer than a quarter knew about it, although many had noticed local weather changes. Among those who knew about global warming, there was a wide variation between nations in belief that the warming was a result of human activities.

By 2010, with 111 countries surveyed, Gallup determined that there was a substantial decrease since 2007–08 in the number of Americans and Europeans who viewed global warming as a serious threat. In the US, just a little over half the population (53%) now viewed it as a serious concern for either themselves or their families; this was 10 points below the 2008 poll (63%). Latin America had the biggest rise in concern: 73% said global warming is a serious threat to their families. This global poll also found that people are more likely to attribute global warming to human activities than to natural causes, except in the US where nearly half (47%) of the population attributed global warming to natural causes.

A March–May 2013 survey by Pew Research Center for the People & the Press polled 39 countries about global threats. According to 54% of those questioned, global warming featured top of the perceived global threats. In a January 2013 survey, Pew found that 69% of Americans say there is solid evidence that the Earth's average temperature has been getting warmer over the past few decades, up six points since November 2011 and 12 points since 2009.

A 2010 survey of 14 industrialized countries found that skepticism about the danger of global warming was highest in Australia, Norway, New Zealand and the United States, in that order, correlating with high per capita emissions of carbon dioxide.

Etymology

In the 1950s, research suggested increasing temperatures, and a 1952 newspaper reported "climate change". This phrase next appeared in a November 1957 report in The Hammond Times which described Roger Revelle's research into the effects of increasing human-caused CO2 emissions on the greenhouse effect, "a large scale global warming, with radical climate changes may result". Both phrases were only used occasionally until 1975, when Wallace Smith Broecker published a scientific paper on the topic; "Climatic Change: Are We on the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming?" The phrase began to come into common use, and in 1976 Mikhail Budyko's statement that "a global warming up has started" was widely reported. Other studies, such as a 1971 MIT report, referred to the human impact as "inadvertent climate modification", but an influential 1979 National Academy of Sciences study headed by Jule Charney followed Broecker in using global warming for rising surface temperatures, while describing the wider effects of increased CO2 as climate change.

In 1986 and November 1987, NASA climate scientist James Hansen gave testimony to Congress on global warming, but gained little attention. There were increasing heatwaves and drought problems in the summer of 1988, and when Hansen testified in the Senate on 23 June he sparked worldwide interest. He said: "global warming has reached a level such that we can ascribe with a high degree of confidence a cause and effect relationship between the greenhouse effect and the observed warming." Public attention increased over the summer, and global warming became the dominant popular term, commonly used both by the press and in public discourse.

In a 2008 NASA article on usage, Erik M. Conway defined Global warming as "the increase in Earth’s average surface temperature due to rising levels of greenhouse gases", while Climate change was "a long-term change in the Earth’s climate, or of a region on Earth."

As effects such as changing patterns of rainfall and rising sea levels would probably have more impact than temperatures alone, he considered "global climate change" a more scientifically accurate term, and like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the NASA website would emphasise this wider context.

See the full article:

Global Warming From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

.png)

.png)

Wonderful site and I wanted to post a note to let you know, ""Good job""! I’m glad I found this blog. Brilliant and wonderful job ! Your blog site has presented me most of the strategies which I like. Thanks for sharing this.

ReplyDeletecontact me @ http://www.buyessays.us/